Virtual Femto Photography

In most of Computer Graphics, light speed is assumed to be infinite: Light sources illuminate their surroundings the instant they are turned on. Since light speed is a lot faster than the average camera shutter speed, this is a reasonable approximation. But what happens when we remove this assumption? If we created a virtual camera that was fast enough, we could capture light as it spreads through the virtual scene! To find out what this looks like, I modified my 2D light transport simulator to render transient effects.

The idea of capturing light in slow motion is not new - in fact, the Femto-Photography project succeded in doing this with physical cameras, which is an impressive feat. Jarabo et al. applied the Femto Photography idea to 3D rendering and rendered beautiful imagery of light moving through virtual 3D scenes. Building on my previous experiments with 2D light transport, it was my goal to apply this concept to 2D rendering.

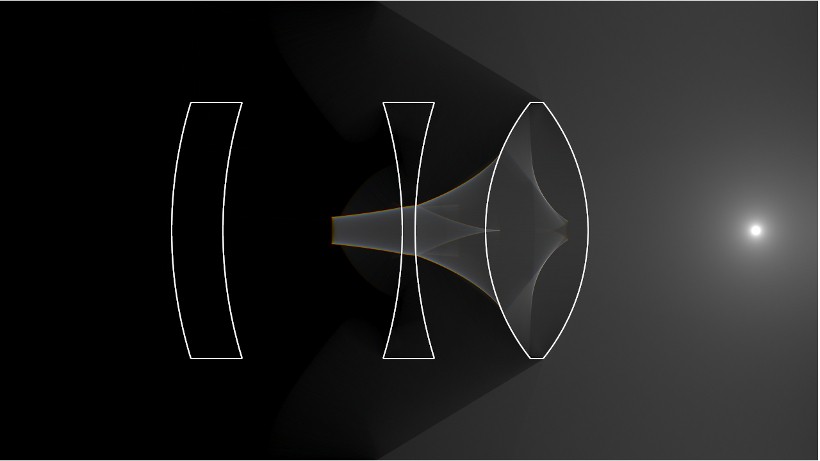

In Monte Carlo raytracing, Femto Photography is very simple to set up. First, we assign our virtual camera a time interval [t0, t1] during which the shutter is open. Rather than rendering all light that reaches the camera, we now only allow light that took between t0 and t1 seconds to reach the sensor.

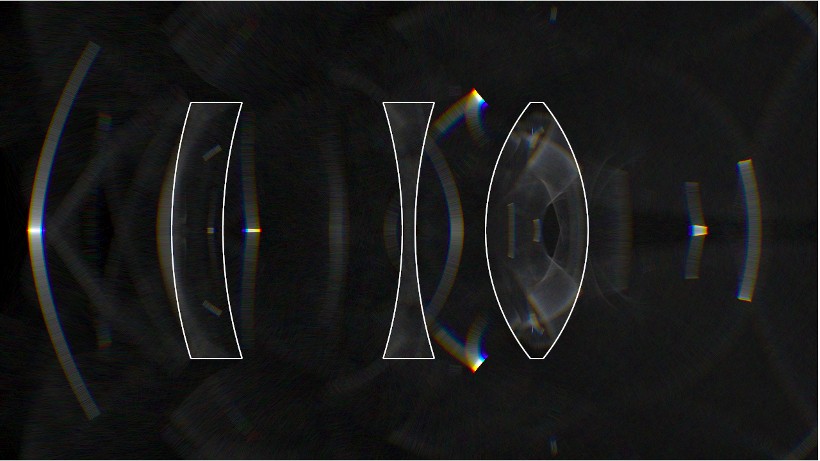

To keep track of time along light paths, I will be using a slightly modified geometric optics model, in which light travels along straight lines at constant speed. This means that we can easily compute how long light takes to travel along a straight segment by dividing the length of the segment by the local light speed. It's worth pointing out here that light speed varies depending on the transport medium - light will travel slower in glass than in air, for example (this is what causes refraction).

A laser pulse entering a participating medium (milk)

Unfortunately it's not immediately clear how to efficiently generate light paths that take between t0 and t1 seconds to travel. Lacking an efficient sampling scheme, the best we can do in 3D is to use existing sampling schemes that disregard the path length and rely on random chance that some of the paths fall within the shutter interval. Since we're essentially throwing away a large part of our samples, this makes Femto rendering very inefficient.

Luckily, 2D light transport does not have this problem: Since the entirety of the path is always visible to the camera, adding a finite shutter time simply amounts to "cutting out" the part of the path that falls within [t0, t1]. This leads to an embarassingly simple algorithm that we can add on top of our existing 2D renderer with only a few lines of code.

At startup, we use a conventional 2D renderer to generate a large number of light paths until the image looks converged. We annotate each vertex on these light paths with a timestamp that describes how long light would take to reach that vertex. We then decompose each light path into its path segments and store these in memory.

This gives us a very large list of line segments, each with a start- and end timestamp. To do a Femto render with this list, we iterate over all segments each frame and check whether the interval spanned by the start- and end timestamp of the segment overlaps [t0, t1]. If it does, we simply move the start and end vertices to the positions on the segment corresponding to times t0 and t1, respectively, and splat the line segment to the screen.

A point light being turned on

This is so simple we could do it in a vertex shader! Simple also means fast in this case: After the initial precomputation, the algorithm runs in real-time. We can easily jump back and forth in time, adjust the shutter width and so forth. Advancing the shutter time each frame allows us to visualize light slowly moving through the scene.

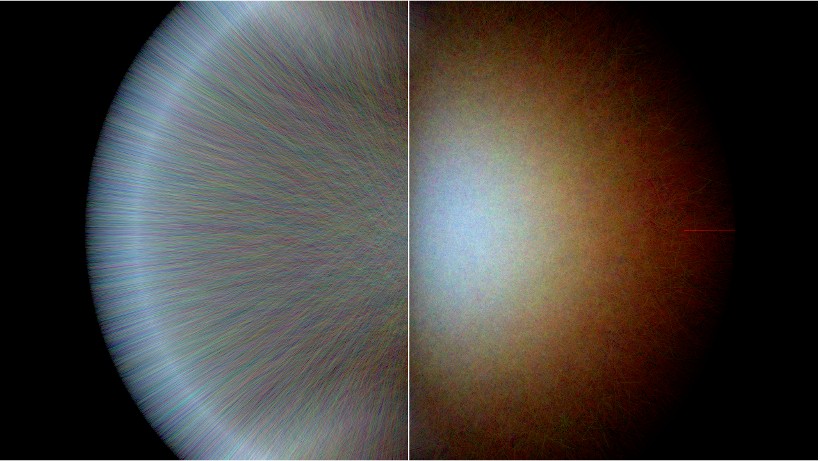

A few of the resulting videos are shown in this article. Note the strong color separation in the first video: Because the index of refraction depends on the wavelength, different wavelengths travel at different speeds through the glass and begin to separate after the first refraction.